LEL 2025: Journey to the Centre of the... Pain

LONDON 09.08.2025 - Cyclist rides to foreign lands in search of lost sanity... none found.

Foreign cyclist spends eighteen months and undisclosed sum preparing for 1,500km international endurance event, injures knee three weeks before departure, goes anyway. Inflicts additional injury on pride and self esteem. Condition worsens hourly until event organisers cancel ride mid-course due to Storm Floris. Rider cycles back completing 700km with what medical professionals would call "contraindicated joint function" and "poor decision-making skills". When asked why, rider cited intent to survey apple crumble at controls. Months later, knee remains injured. Prospects of recovery, dim. Would do again. Apple crumbles rated at 7/10.

One

All healthy riders are the same, but injured cyclists suffer in their own way. That's more or less what I was thinking when I was in the back of the peloton, watching riders that started after me pass with gleaming smiles and shiny kit. I had trained for a sub 100hr ride but was having to quite strictly pace myself to baby my knee.

That first morning was beautiful. Departing from Writtle, early light, crisp air, smooth peloton, the rhythm of wheels and breath and the collective deranged hope that we'd all make it. The first control Northstowe loomed large in my imagination, what do you even do at a control? I had never done an Audax event. I arrived, fumbled through the logistics, ate something, went to get stuff from my bike several more times than needed and left. The knee felt squeamish but fine. Was this going to work?

The next control brought challenging riding, the Fens. Long, windy flats with bad pavement to boot. The knee began its commentary. Someone suggested I take paracetamol pre-emptively. It worked. The Fens felt strange, flat and endless until a chaotic rain made everything feel epic. The subsequent cold brought pain that settled into my knee with no intention of leaving.

By Boston I was hammered. It was clear my training had not been enough. Fifty kilometres to Louth stretched ahead like torture. I fiddled with the bike fit, added washers to pedals to widen my stance, anything to shift the pain somewhere else. It helped. The first abandoners started appearing, laying on the road with blank stares. We exchanged words of encouragement.

After resting outside a church I met Marianne, a French cyclist with a beautifully crafted bike and a pace slow enough that we could ride together and talk. Riding at night was lovely, but the pain was now real. She was pacing carefully as well due to a heart condition. We matched speeds, traded fragments of our stories across the kilometres. Midnight at Louth, both of us knackered, my pain debilitating. She asked to be woken up at 3am (you can do that at controls!) to catch her partner at Hessle in the morning. I ate everything available, including my first apple crumble and proceeded to sleep way too much.

Next morning I took off slowly towards Hessle, realising I was catastrophically bad at control, bad at transitions, bad at eating efficiently, bad at route finding, bad at leaving on time and today with a lot of pain also bad at cycling. To make matters worse I had a flat on the way just when it started to rain. I reached Hessle at around 1300hrs and was immediately told the event was held up due to storm Floris and we could not leave.

I'd been thinking about Paris-Brest-Paris since 2015. Planned for it three times—2015, 2019, 2023—a trilogy of failure where dates and money never aligned, life intervened, the four-year cycle proving impossible to catch. By 2024 I realised I couldn't wait much longer, famous last words. LEL appeared like an answer: 1,500 kilometres, British countryside, no need to qualify in other brevets, 128 hours, next year. I pre-registered for a raffle to ride and to my surprise, I was accepted.

I rebuilt my entire bike for it, new everything, hand picked components, piece by expensive and hard to find piece. The SON nabendynamo hub alone cost an arm and a leg. I built the wheels around the dynamo myself. First wheelset ever. Velocity Dyad rims, DT Swiss double-butted spokes, brass nipples, the works. Spent months staring at the parts before gathering courage to do it. The wheels came out true. Technology would save me! These wheels and the lights attached to them would literally light my way. This was to be the Renaissance of my cycling, the golden age, the Jules Verne version of life where adventure is glorious and preparation prevents catastrophe. Freshly wrapped handlebars pointed north and eighteen months to get ready. What could possibly go wrong?

Two

Hessle. Second day. Storm Floris had arrived with winds exceeding 100 km/h in some of the mountain passes on-route and the event was held up. Four hours, they said. The time would be subtracted from our sheets. No problem. Great, even; enforced rest. The universe intervening on my behalf. I slept and ate.

Departure scheduled for 1530. Determined to learn from past control failures, I woke thirty minutes early, ate something, got my kit together. At 1530 I was at my bike, ready. Staff came to the parking lot and ushered us back inside. The control leader explained we could not leave yet. The wind was still too dangerous. Food was being rationed now. The word "rationed" hung in the air with unfortunate historical weight, rumours of chaos on the subsequent controls due to overcrowding were overheard. We were lucky at Hessle.

More sleep. I had time for philosophical conversations with most of the staff, volunteers and other Audax riders. Met Matt, a brilliant cyclist-volunteer from ACME (Audax Club Mid Essex), a fellow tech geek, good conversation, good man. Talked to many other riders, legends all of them.

At 1930 came the next announcement. The few remaining optimists, myself included because apparently I'd learned nothing, got our kit together again and squeazed into the Lycra, checked tyre pressure and prepared to depart. We had a lot of time to make up for.

1930 and the announcement came. Event cancelled. Storm Floris had won. Tears were barely contained around the room, some riders had trained for years, some had come from other continents, all of us had spent months building hopes and bikes in equal measure. We could not even leave the control until morning. We were trapped with our now rationed apple crumble.

The stakes were no more. LEL was over. Officially.

The training for LEL had been escalating for eighteen months, each ride structurally more absurd than the last, each one a test of some new theory about my setup. I'd done the Goran Kropp-esque ride: bike to Iztaccíhuatl, climb and bike back, more than 3,000 m of climbing on around 200kms... on a cargo bike carrying mountaineering gear with improvised panniers made from old luggage! Epic rides that were supposed to prepare me for epic things, which is precisely the kind of craziness I thought was needed.

My final training challenge were 400 kilometres around Lake Pátzcuaro. Six laps or so depending on route. I started at 5am, the day crisp and promising. First lap: success. Ninety kilometres at 24.4 km/h average. At this rate I would finish early! I stopped, ate, drank, felt invincible. Technology and preparation were working exactly as planned. The wheels I'd built myself were spinning true. This was it.

Second lap began with a slight uneasiness in my right leg. Slight. Barely worth mentioning. When it didn't stop, I frantically checked bike fit—the saddle appeared too low, obviously, that had to be it. I corrected it, measured, remeasured, kept going. The pain didn't leave. It evolved. I kept riding anyway because how could I stop?

Three-quarters through the second lap I stopped at a pharmacy. Bought topical analgesic and paracetamol. Applied both. The pain wasn't crazy bad, I could still pedal, still maintain pace, still finish the lap. By kilometre 170 it was clear I was risking the entire event if I continued. The calculation was simple: stop now, maybe recover in time. Continue, definitely don't.

So I ate something, drank something, and with what seemed at the time like a cold head and rational judgment, decided to stop. Three weeks before LEL. The injury was a challenge from the gods of cycling for my presumption. Ten years of dreaming about PBP, eighteen months preparing for LEL, and my body had chosen this exact moment to file its complaint.

Three

Day three. Three hundred and ten kilometres in, after a kind of rest day. Officially I was supposed to cycle south, back to London, event cancelled, dream abandoned. Instead I decided to rebel against an event that no longer existed by going north. There's a particular kind of motivation that emerges when all rationality has evaporated. I rode north.

The odometer read 350km by the time I reached roughly two-thirds of the way from Hessle to Malton, my planned turnaround point for a 700km total, approximately halfway to Edinburgh. Close enough to half to save face with myself. I considered going farther, alas my knee was not up to it. It was surreal watching other riders stream past in the opposite direction, all of us cycling our own private unsanctioned events, acknowledging each other with nods that meant "yes, this is insane, yes, we're doing it anyway."

The knee felt great at first. Nearly a full day of rest had worked its magic. But eighty kilometres in, now back in Hessle on the southward leg confidence began its familiar erosion, some paracetamol was taken as a remedy. The pain wasn't dramatic, just persistent, a reminder that hope and reality operate on different timelines.

Back through the Humber Bridge with high-speed winds threatening closure. I flew across before they could shut it down, small victories matter when larger ones have been withdrawn. Ended the day at Louth again. Around 140 kilometres. The pattern was repeating: rest, hope, ride, regret?

Food rationing continued because of the chaos and logistical changes. I escaped to find a local pub because in the UK most things worth doing happen in or around a pub. There I met Paul, a fellow audax rider originally from Australia but now a Londoner. We made friends quickly, made plans to meet in London after the event that was no longer an event.

After a couple of pints I counted my blessings and had a decent sleep at Louth. Tomorrow I could feel better, perhaps the knee had settled in a bit more.

After the initial injury came the fiddling-with-the-bike-fit phase. Frantic, obsessive, allegedly scientific adjustments that replaced what should have been training. I fancied myself walking a tightrope between rest and recovery, carefully calibrating the balance. Each ride I would try to improve something: saddle height, cleat angle, pedal washers, improving? But I couldn't really take long enough rides to test any of it anymore. The injury imposed a limitation on long rides, and the departure date was getting close.

I discovered one of my legs is functionally shorter than the other. My left foot is ten millimetres longer. Does that make my body and ride asymmetric? I added an aluminium shim on my right foot to compensate. That was probably it, saddle was too low on one of my legs only, due to the asymmetry. Rode more. Did it work? Hard to say. The pain didn't worsen, which felt like victory. But it never went away, fully, which felt like failure. Schrodinger's knee—simultaneously improving and deteriorating.

I changed so many things, too many things. Saddle height: 74.0 cm exactly, 2mm adjustments and 1 hr riding to test. Right-cleat shim: +2 mm. Cleat angle: heel-in 1°. I kept a blue notebook filled with numbers that promised control. Inseam measurements, hip rock angles under three millimetres, knee tracking over the second toe. Each adjustment was necessary. Each adjustment was futile. Next day it would start again.

By the time I landed in London my knee was swelling up after twenty-minute walks. Twenty minutes. I was stressed, kind of sad, trapped in a cycle: change something, attempt to ride, get hurt, stress about it, rest, change something else, repeat until insane. In theory my bike fit issues were solved (narrator: they were definitely not), barring last-minute adjustments. I put the bike together, torqued the bolts, checked the numbers. Ready, or not LEL was happening.

Four

Fifty-six kilometres after Louth came Boston. I was making reasonably good time, even passing some cyclists. Was the knee getting better? Could this actually work? Hope can be sometimes cruel when administered like that, as I was about to find out.

Around this time a charming little realisation started to creep in and ground my elation: I had most likely blundered my bike fit. These long stretches on the bike had made me slowly come to the conclusion that my saddle was too high. It felt obvious then that my right leg was stretched out on each pedal stroke, my toes having to compensate by pointing downward. Only on the right leg though, body assymmetry and all.

It hit me like a gut punch - after the initial injury I must have compensated too much. I had been over stretching my leg again and again, thuosands of times, 500kms worth of it plus the last bit of my training. Coming to terms with that was brutal. I proceded to passive-aggressively lower the saddle and sure, it felt better, but there was no escaping the fact that I was still injured.

After Boston: the Fens. Somehow we had a headwind. Again. We'd had headwind cycling north, and now headwind cycling south. The laws of nature had suspended themselves specifically to torment LEL riders. The wind on the Fens made quick work of me: flat, endless, wind-swept, I was slowing down.

On one of the fens I was overtaken by a group I'd passed in the peak of my optimism: Shodhan, Daniel, Thomas and Oliver. Daniel kindly asked if I wanted to join their peloton and I didn't flinch. In the wind it makes an amazing difference to ride together, taking turns to break the wind and benefiting from the aerodynamic advantages when riding behind. We became a cohesive peloton, later baptised "Team LEL without E" (a reference to Floris in lieu of Edinburgh).

Together we reached Northstowe. It was some of the best riding I did. Teamwork was great, I was genuinely happy.

We arrived at around 5pm. Most sensible people would stop, rest, eat un-rationed apple crumble, sleep and take it easy, since the event had been cut short anyway-and most did. However, I challenged myself to reach Writtle that night. I wanted an intense ride into the night. The drug of exhaustion that at some stage makes you hallucinate, I am not joking. Sleep deprivation, glucose depletion, and the monotony of cycling on dark roads, a recipe for partially abandoning reality. It's quite enjoyable if you don't overdo it and get run over.

Fifty kilometres south to Henham, the last control. I rode the first part with two Indian riders playing Bollywood soundtracks through a speaker. Loved it in the way only absurdist endurance can be loved, cycling through British countryside at dusk to Bollywood beats.

The days leading up to LEL were torturous in ways the event itself wasn't. My stress level had achieved what engineers call "critical." The knee swelled at seemingly random intervals, people close to me started insinuating the injury might just be in my head, man. I still had to travel from Oxford, our temporary base, to the start point at Writtle. I loaded panniers onto the bike with kit for a week and embarked on a journey involving trains, underground, some actual riding and a spiral of anxiety about whether any of this would work.

I arrived at Writtle a day and a half before the start. Early enough to properly stress.

Registration day: complete party atmosphere. Riders everywhere assembling their beautifully curated machines—vintage Roberts steel, Japanese Panasonics, Dutch velomobiles, someone on a Brompton folding bike looking disturbingly confident. It was great entertainment watching everybody put their bikes and kit together, comparing setups, sharing wisdom earned through previous events. I watched like an outsider at my own event. I'd paid good money for this, trained eighteen months and I felt like an imposter with a broken knee and a bike held together by sheer neurotic energy.

Rode back to my accommodation just before sunset. Still so much to do: routes to download, notes to take, food to pack, alarms to set, backup alarms to set in case the first alarms failed.

Five

Left Henham a bit after 2300. By then pain wasn't limited to my knee. My ass hurt badly, my hands ached, and my Achilles tendon competed with the knee for attention. It was getting painful just to be.

Needless to say I could not go fast. Soon after leaving the control every pedal stroke started to hurt. I needed intense concentration just to stay on the bike. Pain, discomfort, more pain - no fun hallucinations.

The night, however, was splendid. After a while I could kind of separate myself from the pain and observe the event from above, the full moon, the landscape, like I was playing with an action figure of myself. My body moved in agony while my mind floated above, noting the aesthetic quality of the experience, it was beautiful.

I reached Writtle around 0320hrs. Empty control, bit chaotic. No food since the event's organisers were spread thin by the cancellation. But I did manage to buy a beer from a fella that appeared German, obviously. I felt terrible. Also I felt happy. The contradiction made sense in a way that normal logic could not. I'd completed the final 250 kilometres with my injured knee, barely able to function but I'd done it.

I was not in a hurry for this moment to end but I still had five kilometres to get to my accommodation and under the circumstances, it would take the best of me and real effort to ride there. Better get moving. A transformation is expected once this kind of trip ends, what was not expected is I'd arrived weirdly traumatised by the whole affair. No time to enjoy my transformed self or have a fun Jungian dive into the trauma, the event must end, no lingering. The roads, the lights, the bikes, all the friends I made along the way, it was over. Riders return.

Three months after the event came the final diagnosis directly from an MRI, no ambiguity. Tear of the semimembranosus distal tendon. Minimal synovitis and paratenonitis consistent with overuse. The medical language was precise, clinical, definitive. I'd been cycling on a torn tendon for 700 kilometres. My body had been shouting; I'd been muffling the screams with apple crumble.

With hindsight, it seems I had a combination of two things: an overuse injury and a tendon tear. The overuse injury was from eighteen months of training that escalated structurally until something broke. The tendon tear was what happened when I decided to ride with a high saddle anyway, when I kept going after LEL was cancelled, when I completed that final 250-kilometre night, barely able to pedal.

I even managed to make the tear worse after the event by going for a muddy, rocky and unstable run in my very steep surroundings. Because apparently the lesson wasn't clear enough the first time. Because the transformation doesn't mean fixed, just different.

My once in a lifetime success story became a once in a lifetime failure story. I got a medal but really did not finish. I learnt what I'm willing to endure, and what that costs. The tear is still there, I can't ride, I'll lose a whole season and struggle to recover. The understanding of the cost is still forming in my mind. I'm already thinking of the next apple crumble. I will do it again, maybe succeed? If I fail I will do so in novel and fun ways.

Image gallery

Gallery One

Riding to the registration in Writtle, look how hopeful (and painfree) I look.

Riding to the registration in Writtle, look how hopeful (and painfree) I look.

Mid-ride: same person, more pain.

Mid-ride: same person, more pain.

Northstowe, the first control.

Northstowe, the first control.

Gallery Two

Arriving at Hessle; the LEL team made an effort to make every arrival memorable.

Arriving at Hessle; the LEL team made an effort to make every arrival memorable.

Riders hearing about the cancellation at Hessle.

Riders hearing about the cancellation at Hessle.

At 3,700m with Popocatépetl in the background.

At 3,700m with Popocatépetl in the background.

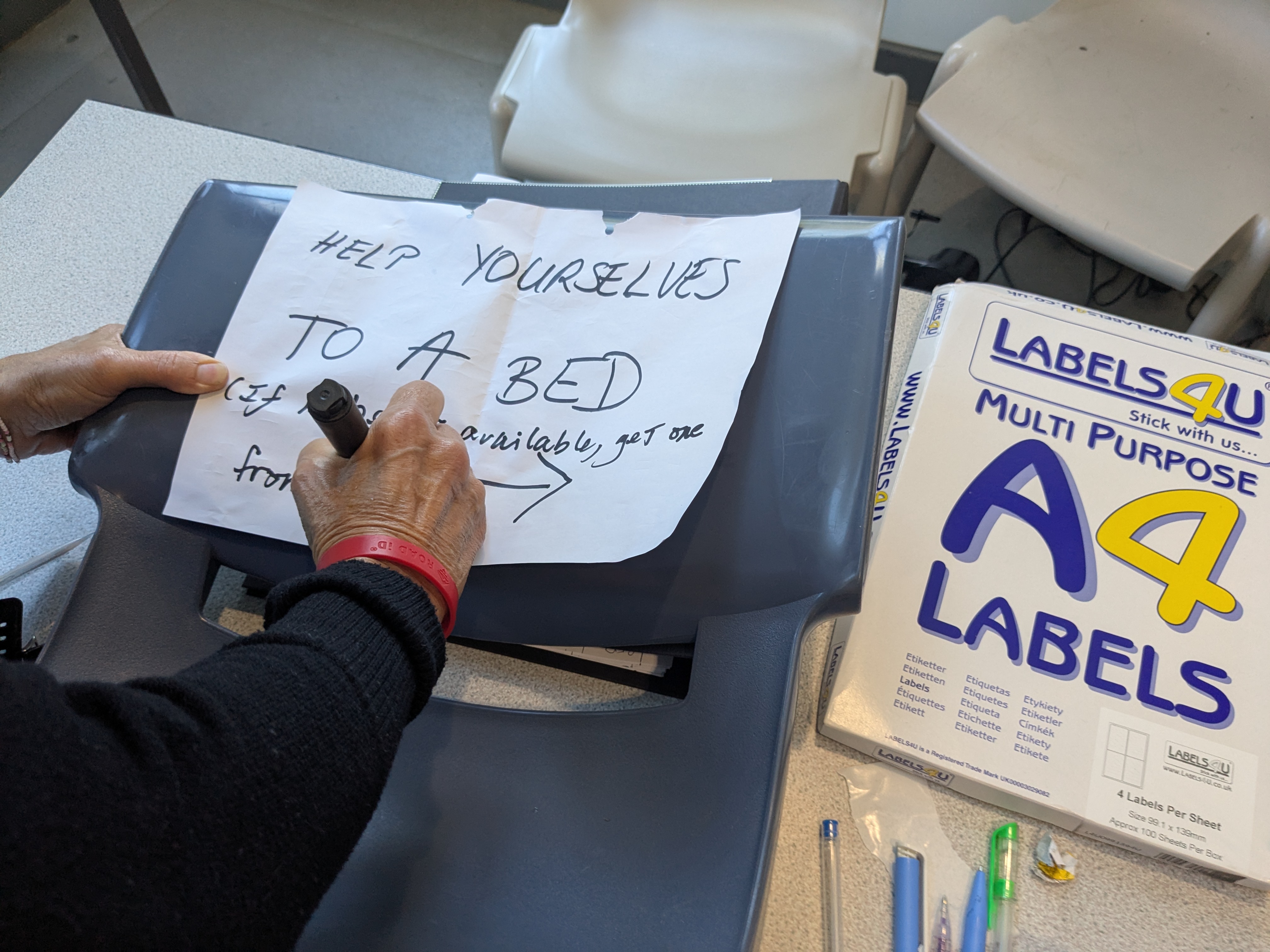

Handmade signage after chaos of cancellation. A radically more laissez-faire approach ensued.

Handmade signage after chaos of cancellation. A radically more laissez-faire approach ensued.

Desolation in the afternoon after the cancellation.

Desolation in the afternoon after the cancellation.

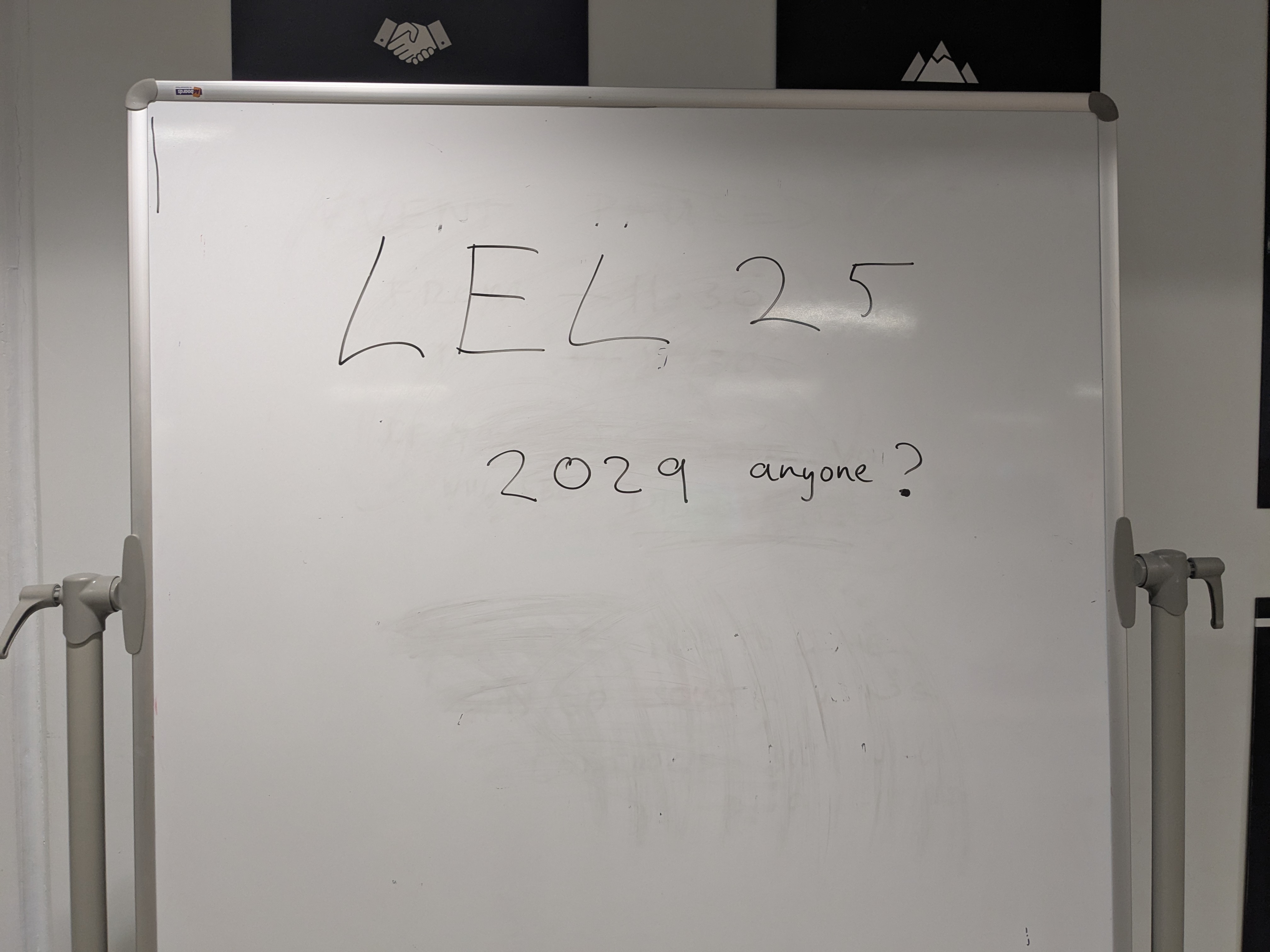

LOL.

LOL.

Gallery Three

St. Mary's at South Dalton. It's round about here that my Odometer hit 350kms and I turned back south again. It was a beautiful place.

St. Mary's at South Dalton. It's round about here that my Odometer hit 350kms and I turned back south again. It was a beautiful place.

The Humber bridge.

The Humber bridge.

We did meet Paul after the event. Went out a couple of times and he was gracious enough to host us for a night before we left. Here he is with Paola and myself at the Borough Market in London.

We did meet Paul after the event. Went out a couple of times and he was gracious enough to host us for a night before we left. Here he is with Paola and myself at the Borough Market in London.

Walking home after the pub in Louth.

Walking home after the pub in Louth.

Gallery Four

Close to Louth in the Lincolnshire Wolds.

Close to Louth in the Lincolnshire Wolds.

Oliver and myself riding in the Fens.

Oliver and myself riding in the Fens.

Team LEL without E at the finish line, boasting our medals.

Team LEL without E at the finish line, boasting our medals.

Gallery Five

Getting close to Writtle cycling at night. Note the moon.

Getting close to Writtle cycling at night. Note the moon.

Arriving at Writtle in the middle of the night.

Arriving at Writtle in the middle of the night.

At the finish line, 03:19hrs 7th August 2025.

At the finish line, 03:19hrs 7th August 2025.

Copyright © 2025 Everardo J. Barojas. All rights reserved.

License: This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

You are free to:

- Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format

- Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially

Under the following terms:

- Attribution — You must give appropriate credit to Everardo J. Barojas and wwwww.climb.mx (with a link to the original post), provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.